US unemployment insurance isn’t ready for the next recession

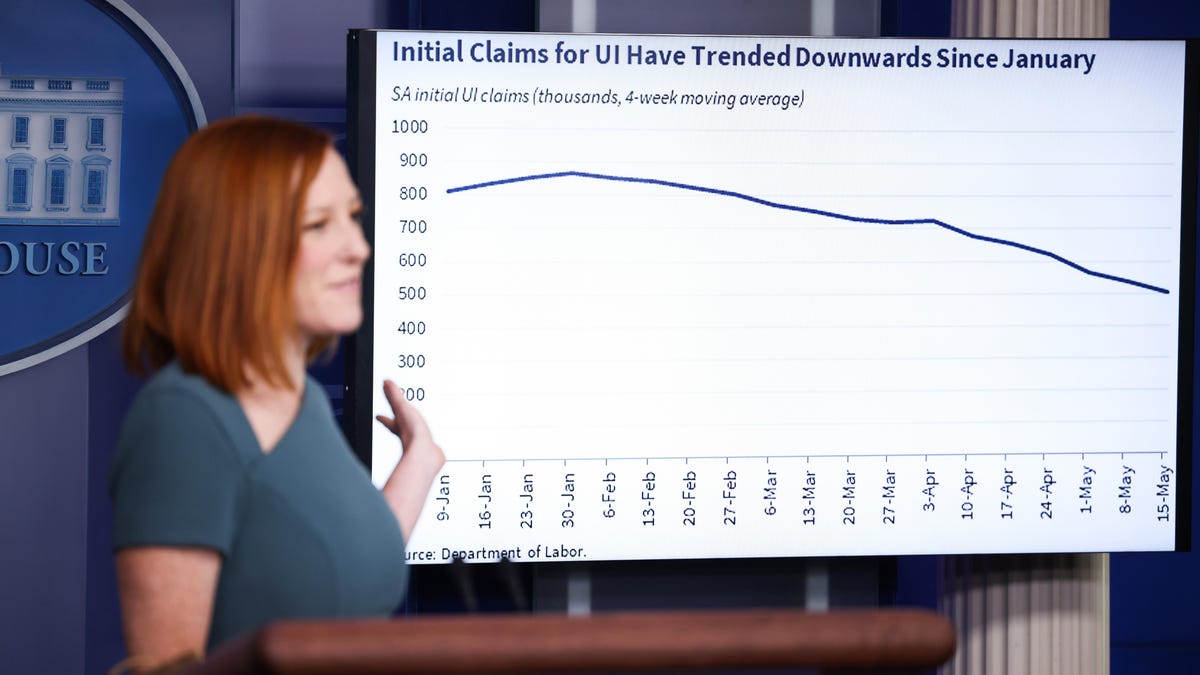

The Fed keeps hiking, the markets keep sinking, and winter is coming: Economic forecasters fear a recession is on the way.

In the US, Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell made clear this month that his policy is centered on fighting inflation, with Fed officials suggesting that the unemployment rate could reach 5% before the bank lets up on interest rate hikes. That would mean more than 1.5 million Americans thrown out of work.

As the debacle in the UK shows, it’s never a good idea for a country’s lawmakers to be at cross purposes with its central bank. In the US, however, the Biden White House and Congress have not prepared adequately for a recession induced by the Fed’s inflation fighting. In particular, glaring flaws remain in the unemployment insurance (UI) system tasked with keeping people who lose their jobs from falling into poverty—and dragging the economy down further.

During the pandemic-driven recession of 2020, unemployment insurance was a key tool that softened the blow of public health restrictions and helped lead to one of the fastest employment recoveries in modern history. But the experience also reminded us of what should be corrected. Consider…

Fraud was serious.

US auditors suspect more than $45.6 billion of UI payments during the pandemic went to fraudsters using stolen social security numbers and other techniques to apply for benefits and then disappear. One important reason the system is so vulnerable to bad actors is that it is administered by the states. Even investigating past crimes requires a special effort by the White House to collect data from each state. Many states have underfunded their UI bureaucracy, with some states scrambling to adapt computer systems that rely on obsolete programming languages.

States cut support.

The federal government effectively finances states as they deploy UI, but that creates troubling incentives. State trust funds are the first source of money for UI, but once they run out, the federal government provides states with low-cost loans. The idea is that during good times, the states will refill their trust funds, but often the opposite happens: Lawmakers reduce eligibility for UI and the length of time it is available in order to reduce the amount they need to save. We saw this after the financial crisis, and it’s already happening post-pandemic. It will leave future unemployed workers with less support, and also contribute to the confusing patchwork system of UI across the country. For example, in Alabama, there is a maximum of 14 weeks of UI available to workers, while in Georgia there are 26 weeks.

Gig workers need support.

UI is designed for workers who are employed by other people, but 10% of US workers are independent contractors or self-employed. During the pandemic, Congress passed a law that temporarily extended benefits to these workers, but it ran into significant administrative difficulty because state unemployment agencies weren’t prepared to deal with the challenge of verifying income from tax forms used by these workers.

UI should be an automatic stabilizer.

During economic crises, US lawmakers have extended and enhanced UI payments. But these decisions are typically not well timed and often held up by political brinksmanship. That makes the funding less effective when it reaches people who need it, and slows economic recovery. It would be more efficient to make more generous UI payments automatic when economic data, like a three-month average unemployment rate, shows that the labor market is in unusually dire straits.

How to fix UI.

There are good ideas to fix all these problems, starting with better funding: The US hasn’t increased the amount of a worker’s salary, the first $7,000, that can be taxed to fund unemployment since 1983. When the program began in 1933, the taxable wage was about $50,000 in today’s dollars. Raising the taxable amount and lowering the rate could result in enough funding to administer the program more effectively and avoid waste and fraud.

Two Democratic senators, Oregon’s Ron Wyden and Colorado’s Michael Bennet, have proposed legislation that addresses most of these flaws, and puts a floor of basic standards underneath the current patchwork system. It has garnered the support of 21 other senators, but none of them are Republicans. The bill is unlikely to be enacted without at least nine or 10 Republican votes, which in turn suggests that our creaky UI system won’t change much in advance of the next recession. It’s possible that the measure could have passed through the reconciliation process, which allows certain legislation to be enacted by a simple majority, but the measures were not included in the Inflation Reduction Act that became law in August.

And while the Wyden-Bennet bill contains common-sense measures to improve UI, it doesn’t begin to approach the kind of sweeping changes that would bring the system into the 21st century. Something like, say, a federally-administered program that relies on tax data to automatically deliver UI benefits to eligible recipients, perhaps administered by the Social Security Administration, instead of creating more than 50 redundant bureaucracies across the country.

Information contained on this page is provided by an independent third-party content provider. This website make no warranties or representations in connection therewith. If you are affiliated with this page and would like it removed please contact editor @producerpress.com